The novel coronavirus has spread to over 60 countries alongside its darker cousin: false information about the disease, how it spreads and how we can protect ourselves against it.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has called it an “infodemic” as misleading or incorrect information is spreading faster than the virus. Whether it’s quack doctors pushing fake ‘cures’, conspiracy theories used to undermine opposition governments, hoax “symptoms” or funny memes, they create an environment that makes it hard to trust what we find online and add to the global panic and anxiety around the problem.

“Stigma, to be honest, is more dangerous than the virus itself,” said WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

When we come across content online that causes strong emotional reactions — like panic or fear — we can accidentally share things without stopping to think and check whether they’re accurate.

Agents of disinformation take advantage of this and create content designed to make us panic-share stories, angry-post reactions, forward happy puppy stories, and everything in between.

But we can fight the information disease together. Here are five quick things we can do to verify content online before we share.

Some stories are too good to be true

Story published by the Mail Online of unverified rumours that a creative Australian couple quarantined off the coast of Japan had two cases of wine delivered by drones

False and misleading stories spread like wildfire because people share them. Lies can be sexier than the truth.

A group of researchers from MIT found in 2018 that stories that trigger an emotional response are shared way more than straight news stories. Added to that, neuroscientists have confirmed that we are more likely to remember stories that make us angry, sad, or laugh.

In February, an Australian couple was quarantined on the cruise ship off the coast of Japan. They developed a following on Facebook for their regular updates, and one day claimed they ordered wine using a drone. Journalists started reporting on the story, people shared it on social. The couple later admitted that they posted it as a joke for their friends.

This might seem trivial, but mindless resharing of false claims can undermine trust overall. And for journalists and newsrooms, if readers can’t trust you on the small stuff, how do they know to trust you on the big stuff?

Tips:

- If a story is too good to be true, too funny, too infuriating, too sweet, too outrageous, it probably is. Go to the source before you post.

- Remember that journalists can fall for this too — so just because other news outlets are reporting a story doesn’t mean they verified it with the source.

- For more websites and tools to verify content online check out our verification toolkit and our Guide to Verifying Online Information.

Remember, not all research is created equal

Just because something has a chart or a table attached to it, doesn’t mean the numbers and the science behind it is solid.

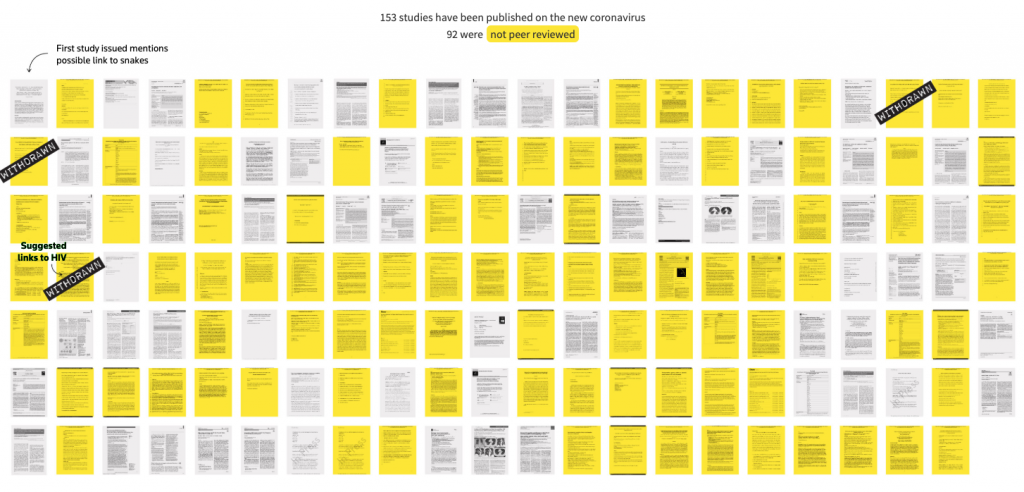

Reuters had a look at scientific studies published on the new coronavirus since the outbreak began. Of the 153 they identified, 92 were not peer-reviewed yet and some included some pretty outlandish and unverified claims, like linking coronavirus to HIV or snake-to-human transmission.

The problem with “speed science”, as Reuters called it, is that people can panic or make wrong policy decisions before the data has been properly researched.

Source: Reuters, 2020. Speed Science: The risks of swiftly spreading coronavirus research

So if you come across a chart, a table, a stat, or any number related to Covid-19, ask yourself:

Tips:

- What’s the source? Where did those numbers come from?

- Always consult official sources that aren’t part of any particular government.

- The WHO’s Coronavirus page has updated stats and recommendations.

- John Hopkins University keeps an updated map.

- For journalists, Journalist’s Resources does helpful roundups of verified research.

by Laura Garcia, First Draft

Related posts

Magazine Training International’s mission is to encourage, strengthen, and provide training and resources to Christian magazine publishers as they seek to build the church and reach their societies for Christ.